Angak’china known as the First Kachina and/or the Beautiful Kachina, commonly referred to as the Long Beard, Long Hair and even Loose Hair.

This carving is being offered to our Two Graces collectors at $9,500.*

Hopi Kachina aka Katsina 8” tall ca.1880-1910 red cottonwood root, clay, mineral paints, feathers and cotton string

The height of eight inches, is a standard size, it has a very large presence whether you have a collection of several Kachina Dolls or only this one, it is a knockout. A true American Folk Art carving, simple and well made this antique Kachina Doll will bring lasting joy to any collection.

Referred to as a Volz style kachina doll carving from the time frame of 1870-1910. The trading post of Frederick Volz was located at Canyon Diablo near the First Mesa of the Hopi Villages. A large collection of these dolls were acquired by the Fred Harvey Company in 1901. Among these dolls there is a ‘dance motion’ created by the carver which this doll truly appears to have.

The deep green pigment of the face indicates an early carving, the later usage of a blue color (using a fugitive ground flora material) often fades to a soft warm grey.

The Angak’china’s purpose is to bring rain, it is a common occurrence that during their dancing that rain will begin to fall. This of course may be due to when they dance which is typically during monsoon season. The long-beard is also seen at other Pueblo villages and is a popular entity at Zuni Pueblo. During a 1990 visit with several friends to Zuni a Kachina dance was about to take place, over fifty Longbeards along with 50 Mudhead Koyemsi Kachina figures came out into the Zuni Plaza and began to dance in the rain. I foolishly asked if the dance would take place due to the rain. Told that the point of the dance was for there to be rain, (I tend to not ask such questions any longer). The ‘singing’ (which sounded like a low hum) is meant to bring positive messages of Life to the Pueblo people.

A Thorough Condition Report

The loose hair represents gently falling rain, the row of various squares of colors across the lower portion of the mask representing a rainbow. The top portion of the head at the hairline is quite worn and chipped, oxidation of the cottonwood shows this to be quite old damage. Remnants of feathers, cloth(?) and string protrude from the top of the head.

Over the missing black hair fringe (Sokum’kalmungwa) there would have been soft white eagle feathers hanging from the three knots of the string at the lower portion of the face mask. Where the beard once was the paint is very much worn from the abrasiveness of the horsehair rubbing against it.

Overall the face mask (maskette) is painted a green known as Sakwa, usually a copper carbonite minerał paint, or a terre verde, chromium oxide, malachite. Other theories reference the mixing of a yellow ochre pigment with an indigo. Green (not blue) of the masquette is referenced in the Smithsonian publication of 1899/1900 Twenty-First Annual Report.

A cotton string was attached around the neck to facilitate hanging the doll in a Hopi home. The string and entire body of the doll was then painted over with the traditional tuma, white clay used as a wash or ‘primer’. The string at some point broke away but in the front is still embedded in the clay wash. An eye hook was put into place in order to hang the doll, probably by Max Weber. A fresh length of cotton string has been tied in place, anyone acquiring this carving may of course remove the eye hook, however a professional restorer should be consulted.

The tuma filler at the underarm areas has worn away, but each arm is firmly attached. There is an indication of old rabbit skin glue (rabbit skin glue has a telltale brown look to it) in the armpit of the right arm. The left forearm is missing, this is an old break from being played with by the original child owner. The complete right arm slopes gently to an early version of a hand, which is sans any indication of wrist or fingers. Breakage and lost arms is common among all kachina dolls, examples of early dolls will more than likely have missing parts. If a new owner chooses to have the forearm restored this can be done by a **professional restoration person. Personally I have chosen to leave it as is.

The painted zigzag or rick-rack sash at the waist is crisp with a continuous lyrical flow to it. At the right side of the kilt the classic woven design with cloud symbols has similarities to other dolls made during the time frame of 1880-1920. The kilt itself is asymmetrical, (this was pointed out to me by the only other person we’ve shown the doll to).

Provenance

From the estate of Joy Weber (1927-2016) Santa Fe resident, handed down to her from her father the artist Max Weber (1881-1961).

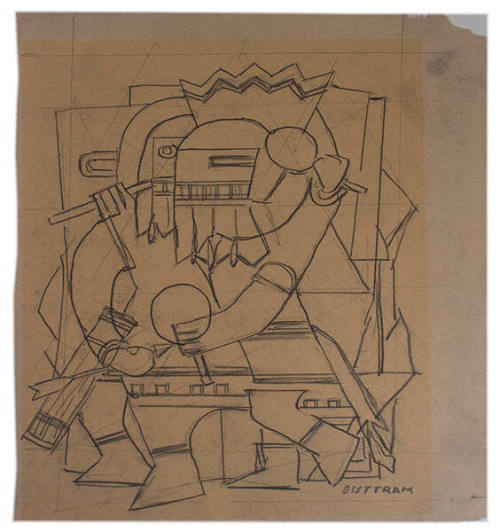

Weber was known for having brought the styles of Cubism and Fauvism to the United States. After attending the Pratt Institute of Art in Brookly, NY, in 1905 Weber went to Paris, where he continued his studies at the ateliers of the Académie Julian, the Académie Colarossi, and the Académie de la Grande Chaumière. His early mentors, teachers and friends included Arthur Wesley Dow, Henri Matisse, Henri Rousseau, Guilliame Apollinaire, Pablo Picasso & Robert Delaunay. The ethnographic collections he saw in Europe were an influence on him as they were for many of the artists of the period. Ethnographic works were so influential on the artists in the early to mid-1900's that the Museum of Modern Art presented an entire exhibition of the artworks they inspired alongside the original material. The two volume publication for this exhibit is a vast resource, 'Primitivism in 20th Century Art, Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern' William Rubin 1984.

From 1909-1911 he became a part of the Alfred Stieglitz circle of artists exhibiting at Gallery 291. He exhibited at the Society of Independent Artists, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Museum of Modern Art and the Jewish Museum. During the early 1920’s at the Art Students League in New York, Weber taught art classes to a prestigious ‘who’s who’ of student artists.

While in Paris, Gertrude Stein is known to have purchased a Weber painting. Weber’s Taos connection is to the Grande Dame herself, the ever influential Mabel Dodge Luhan who purchased three of his paintings in NYC. Many years later one of these paintings was included in the 2017 exhibition at the Harwood Museum “Mabel Dodge Luhan and Company: American Moderns and the West”. His connections to Andrew Dasburg, Georgia O’Keeffe, Alfred Stieglitz, and Mabel Dodge Luhan put him in the realm of what some consider the Taos circle of artists, although it is thought that he turned down an invitation to visit Taos by Mabel and was not directly involved with any of the Taos groups he was very much aware of them. It would be best to consider him in ‘The Circle of Stieglitz’. The writings of Weber are thought to have influenced Georgia O'Keeffe in her abstract 'Infinity' studies.

Examples of Southwestern Pueblo Pottery are in a few of Weber’s still life paintings.

How, where and why Weber would have collected this particular Kachina doll is somewhat baffling until you begin to understand his deep spirituality and delve into his writing “Essays on Art” 1916.

The collections (in particular the Cabinet of Curiosity style collections) in Europe particularly in Paris along with Museums across Europe were known to include Kachina Doll carvings. The cubist artists in particular, greatly admired carvings by the Hopi & Zuni people of the Southwestern United States.

To see a thing is to see its inherent spirit… To see an artwork casually or en passant, is a very pleasant experience; but to come in touch with the vision, the spirit of its maker, is seeing in participation, and then it is not a gratification but an exaltation.

Max Weber for Photographic Art, 1916

*Due to the Provenance, Age and Condition of this carving we believe the price point to be below current value.

** Professional Restoration, means just that, this is not a do-it-yourself project. I have been restoring Kachina Doll carvings and other historic wooden items since 1981.

‘THE FOURTH DIMENSION FROM A PLASTIC POINT OF VIEW’

In plastic art I believe, there is a fourth dimension which may be described as the consciousness of a great and overwhelming sense of space - magnitude in all directions at one time, and is brought into existence through the three known measurements. It is not a physical entity or a mathematical hypothesis, nor an optical illusion. It is real, and can be perceived and felt. It exists outside and in the presence of objects, and is the space that envelops a tree, a tower, a mountain, or any solid; or the intervals between objects or volumes of matter if receptively beheld. It is somewhat similar to color and depth in musical sounds. It arouses imagination and stirs emotion. It is the immensity of all things. It is the ideal measurement, and is therefore as great as the ideal, perceptive or imaginative faculties of the creator, architect, sculptor, or painter. Two objects may be of like measurements, yet not appear to be of the same size, not because of some optical illusion, but because of a greater or lesser perception of this so-called fourth dimension, the dimension of infinity. Archaic and the best of Assyrian, Egyptian, or Greek sculpture, as well as paintings by El Greço and Cézanne and other masters, are splendid examples A Tanagra, Egyptian, or Congo of plastic art possessing this rape sualtof a Canagra, Fee, anile ongo, mediocre piece of sculpture appears to be of the size of a pin-head, for it is devoid of this boundless sense of space or grandeur. The same is true of painting and other flat-space arts. A form at its extremity still continues reaching out into space if it is imbued with intensity or energy. The ideal dimension is dependent for its existence upon the three material dimensions, and is created entirely through plastic means, colored and constructed matter in space and light. Life and its visions can only be realized and made possible through matter. The ideal is thus embodied in, and revealed through the real. Matter is the beginning of existence; and life or being creates or causes the ideal. Cézanne's or Giotto's achievements are most real and plastic and therefore are they so rare and distinguished. The ideal or visionary is impossible without form; even angels come down to earth. By walking upon earth and looking up at the heavens, and in no other way, can there be an equilibrium. The greatest dream or vision is that which is re-given plastically through observation of things in nature. "Pour les progrès à réaliser il n'y a que la nature, et l'œil s'éduque à son contact." (*For progress to be made there is only nature, and the eye is educated through contact with it). Space is empty, from a plastic point of view. The stronger or more forceful the form the more intense is the dream or vision. Only real dreams are built upon. Even thought is matter. It is all the matter of things, real things or earth or matter. Dreams realized through plastic means are the pyramids and temples, the Acropolis and the Palatine structures; cathedrals and decorations; tunnels, bridges, and towers; these are all of matter in space-both in one and inseparable.

Max Weber for Camera Work 1916