Dorothy Brett, a labor of Love for 100 years in Taos

“I have thought a sufficient measure of civilization is the influence of good women.”

Ralph Waldo Emerson

During the third week of March 1924 the Honorable Dorothy Eugénie Brett (10 November 1883 – 27 August 1977) arrived in Taos, New Mexico with Freida & D.H. Lawrence. The original intent was for Lawrence "to create a utopian society he called Rananim” (Dorothy Brett in an interview), He had attempted to recruit members of the Bloomsbury Group and its circle of friends. Brett was the only one who made the journey with the Lawrences.

Throughout her time in Taos, people who made pilgrimages to the Lawrence Ranch and to visit with Brett came mostly to hear her recollections of Lawrence who she loved to reminisce about. In his writings Lawrence used broad strokes of references to his circle of friends, sometimes thinly veiled, he included Brett as a character in a few of his stories such as The Plumed Serpent and The Last Laugh. During her time with the Lawrences, staying in a tiny cabin at the Ranch in San Cristobal, Brett was tasked with typing the handwritten manuscripts of Lawrence.

As written by Mabel Dodge Luhan 1933 in “Lorenzo in Taos’

“What is it about Brett you like?” DH Lawrence replied: “I don’t know. Somehow I feel that she has something of a touchstone about her, that shows up things… I can’t explain it exactly.” MDL: “…Brett had evolved a costume for the West, consisting of a very wide-brimmed sombrero…, high boots, with a pair of men’s corduroy trousers tucked into them and, in the right leg, a long stiletto (knife)! …the natives (hispanics) were afraid of her, and one of the old Mexican (men) refused to drive her up to the ranch… Señorita with dagger very dangerous! he told Tony (Lujan).”

In Taos, Brett befriended the indigenous people of Taos Pueblo which she became enamored with, many of whom were close personal friends and whom she relied upon as confidants. Without these friendships she would never have survived on her own, together they had strong bonds of friendship. At the time of her arrival, there were already a well formed group of men, known as the Taos Society of Artists creating paintings of the Native Peoples in a variety of manners.

Brett rarely spoke or wrote about her paintings, either preferring to speak about DH Lawrence, friends and acquaintances or at times notes about her travels. One statement she did make at some point was to recommend her paintings be hung in ones bedroom where the morning light and evening light forever changed. In order to gain some insight of her paintings I’ve selected pieces of writing by others and whenever possible quotes from Brett about her body of work, the most pertinent have been chosen and included here.

“For years now I have been painting the Indians. I have painted their beautiful Ceremonial Dances, in order to make a record of them as they do not allow them to be photographed or any drawings made of them. I have done this to preserve a record in case in course of time the American way of life entirely absorbs the Indians and they cease to dance. I have to memorize the dances and paint them entirely from memory. they are months to paint. They are records of a way of life and of a culture.”

She had brought with her to New Mexico a style of painting, swooping arcs, formalized and centrally focused design, bright primary colors, and a belief that painting was an ‘inward spiritual beauty’ that she washable immediately to project upon the impassive Indian. A number of Indians became her friends over the years, not an everyday phenomenon even in present day Taos, and Trinidad a particularly close friend. He guided Brett in her painting of the religious ceremonies, at times providing detail, at times holding her back from too great an intrusion, always a discreet mediator and protector in her dealings with the Pueblo. It was and theoretically is, though the restriction is often nowadays overlooked or abused, forbidden to record ceremonies and dances and, from time to time, cameras have been smashed and sketchbooks confiscated. Brett herself liked to recall that, soon after her establishment in Taos, the Pueblo elders heard of her work and, unannounced and uninvited, a group of Indians walked into her house, contemplated her paintings for a long time and then left. A few days later a second blanket-wrapped delegation walked in and, once again, stared long at the paintings, one of which was an attempt to record the most important date in their religious calendar, the annual ceremony at Blue Lake, a sacred place hidden high in the mountains behind the Pueblo. By then Brett was genuinely frightened. When, at last, they turned to leave, one of them indicated the Blue Lake painting and spoke, just two words. “Never again.”

‘Brett from Bloomsbury to New Mexico, a Biography’ Sean Hignett 1983

Much like a poet, Brett painted from memory, from a feeling of place and events she’s witnessed. She was not allowed to photograph, paint or draw at Taos Pueblo, or any of the villages in northern New Mexico, as per tribal rules. Although Brett was not known to ever write poetry, there is an affinity to the artist William Blake in the narrative storytelling quality and translucency of her paintings. Where Blake created imagery based on myths, Brett created paintings based on things she witnessed. In her storm & rainbow paintings there is an obvious influence from the paintings of JMW Turner through the scumbling paint and thin incoming stormy veil she forces you to look through the storm at what is in that landscape.

To break down her many years of painting into categories, Brett’s subject matter included Pueblo Ceremonials, Taos Blue Lake, 2 & 3 Pueblo (singers) figures, Rainbows/Storms, Vortex/Abstracts, Stokowski & Portraits, DH Lawrence, Bahamas & Sea Life, Potboilers (small quick painting sketches, sometimes revisiting subject matter she’d painted on a larger scale), Drawing Studies and Detail Paintings of specific objects.

The following works from our Brett Collection are available at Two Graces Taos through January 20, 2025.

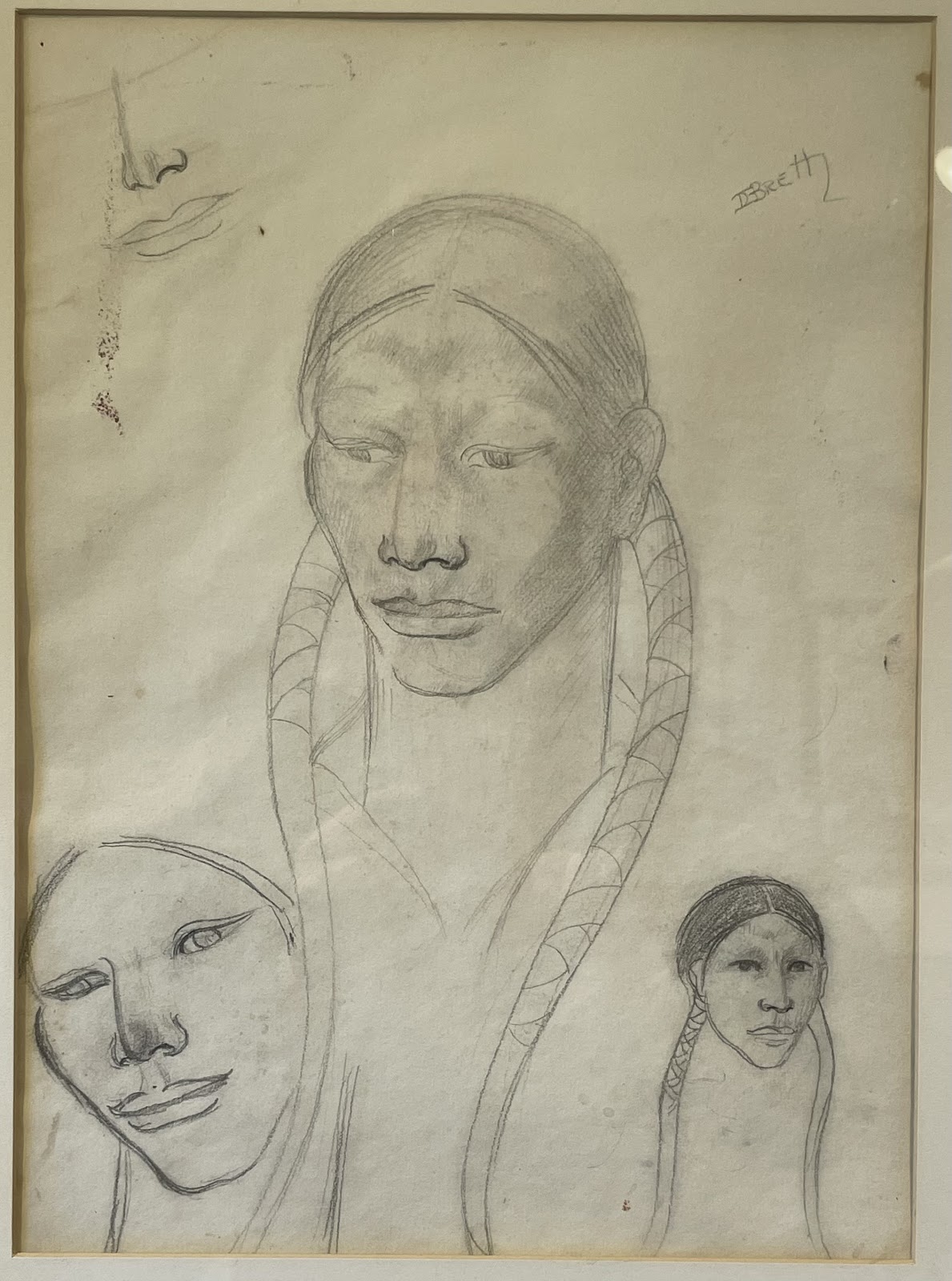

“Drawing Studies of Taos Pueblo Man” 10” x 13”

(framed 16” x 19.5”)

(possibly Trinidad Archueleta)

pencil on paper

$2,100.

Tower Beyond Tragedy

quote on punched tinwork 20” x 6”

(tinwork attributed to Brett,

similar to Phoenix tinwork at DH Lawrence Ranch)

The Complete Quote Reads:

ELECTRA: I can endure even to hate you,

But that's no matter. Strength's good. You are lost. I here remember the honor of the house, and Agamemnon's. She turned and entered the ancient house. Orestes walked in the clear dawn; men say that a serpent Killed him in high Arcadia. But young or old, few years or many, signified less than nothing To him who had climbed the tower beyond time, consciously, and cast humanity, entered the earlier fountain.

“The Tower Beyond Tragedy” (excerpt, last stanza) 1924 Robinson Jeffers

$500.

“Rock Pool” 13.25” x 25”

oil painting on board, assemblage w beads,

shells, broken glass & sequins

1963

$2,400.

“Lady Dorothy Brett”

portrait by Julian Robles 1969

20” x 22” Charcoal on toned paper

(28.5” x 30.75” framed)

$1,800.

“Taos Collects Brett”

Catalogue of Brett in Taos

1967 5.5” x 8” printed pamphlet

(12.5” x 14.75” framed)

$100.

DH Lawrence Crucified 1963

& Deer Dancer (Tony Lujan) on Kiva Ladder 1965

Drawing (double sided)

8” x 10” pencil on paper

(studies for “The Last Laugh” depicting DH Lawrence Crucified and a depiction of Lawrence as the mythical Pan & “Taos Deer Dancer Greeting the Sun” verso, the figure cloaked in the skin of a deer is considered to be of a young Tony Lujan)

(framed 12” x 14.5”)

$2,100.

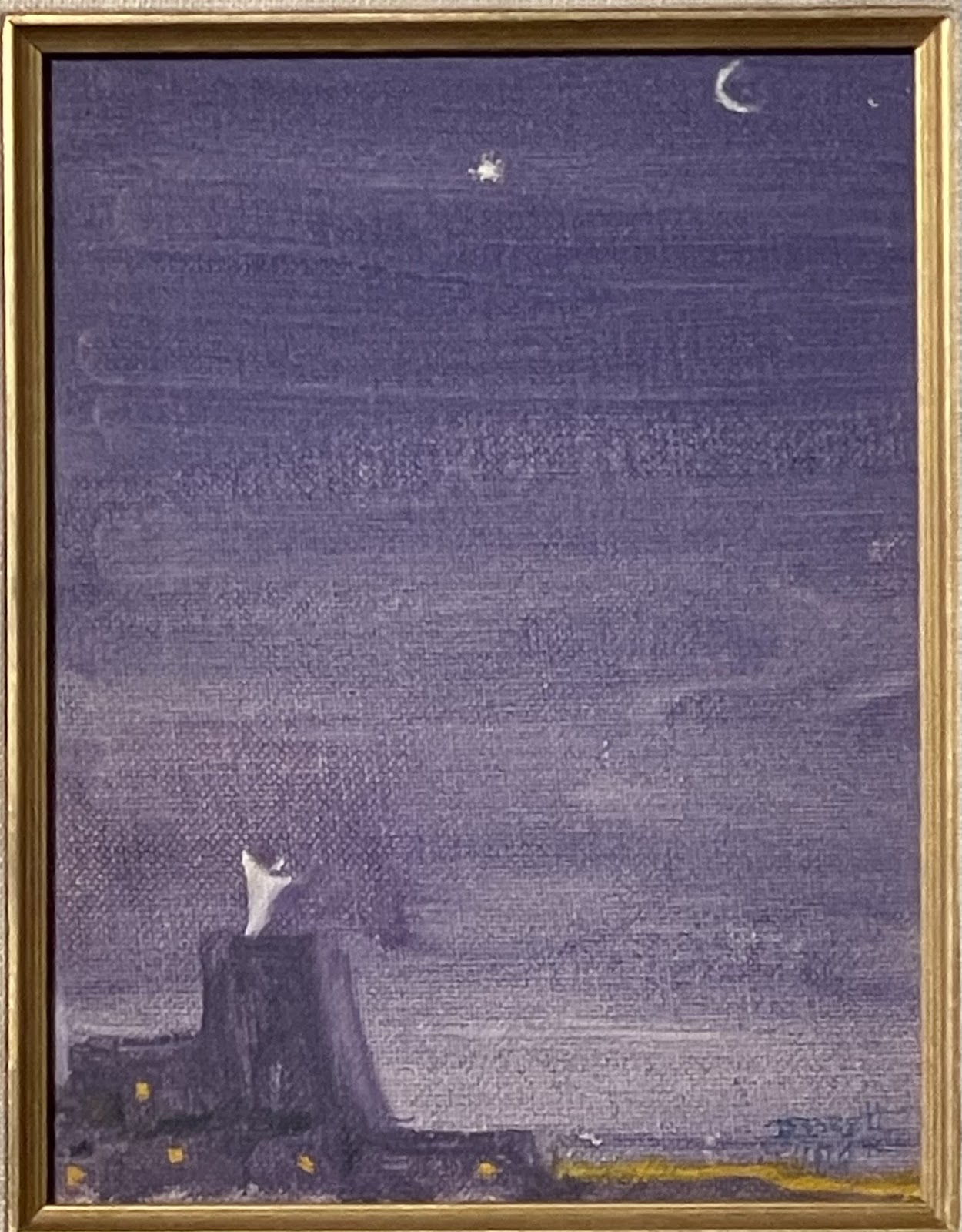

“Greeting the Winter Moon” 5” x 7”

(framed 12.75” x 14.25”)

oil painting on board

(dedication on verso: A Merry Christmas & Happy New Year Brett, John and Little Reggie)

$950.

“Snow Storm at Taos Pueblo” 20.5” x 17.25”

oil painting on board

1963

Provenance: Purchased at Gallery A Taos ca.1964 by George Henderson (1917-1997), former head of the Fine Arts Department of the Dallas Public Library & President of the Dallas Prints and Drawing Academy

$3,600.

Note to Brett Family Members

4” x 6” on Index Card

(9.25” x 7.25” framed)

“To James Brett one of the descendants of the three Brett Brothers who came over to this country& settled. Two in the east, one in the South West. From DE Brett of the family who stayed home…”

$100.

Handwritten Letter from Brett to Boyce

regarding a visit to Mabel Dodge Luhan 8” x 10.5”

on Tower Beyond Tragedy letterhead

(12” x 15” framed)

SOLD

“Jamaican Women” 9 3/4” x 13 1/4”

Oil on paper

1950 9 3/4” x 13 1/4”

This painting is currently available through the Owings Galery, Santa Fe 505-982-6244

It is included in the biography “A Life in Full, Millicent Rogers” Bachrach, Murphy, Nasse 2012 on page 161

*Please Note:

John Manchester as Brett’s gallery director found that many of the works Brett had created had not been signed and dated upon completion. This led to his request that she sign and date artworks that were to be exhibited and sold. Many of Brett’s art is dated in the 1960’s not because she was much more prolific during this time frame but because of the Manchester request. Unable to recollect when works were created, she signed and dated them during this 1960 time frame.

Our exhibit also includes some of the ephemera associated with Brett.

During her lifetime in Taos, Brett settled into various accommodations, (six at my count) a timeline of which is vague at best, first residing at the Blue House of the Mabel Dodge Luhan estate, then the tiny cabin at the Lawrence Ranch (aka the Kiowa Ranch, the Flying Heart Ranch & Lobo Ranch), later she lived in a similar cabin at the Hawk Del Monte Ranch by a mountain stream. Brett for a time lived at the Nicolai Fechin estate, eventually she built a two story home on the Hawk Ranch property which she called the ‘Tower Beyond Tragedy’. With winter season in the Taos Sangre de Cristo Mountains being quite harsh, Freida Lawrence gifted a plot of land to Brett, closer to the Taos Pueblo, in the valley where she built what is known as The Brett House.

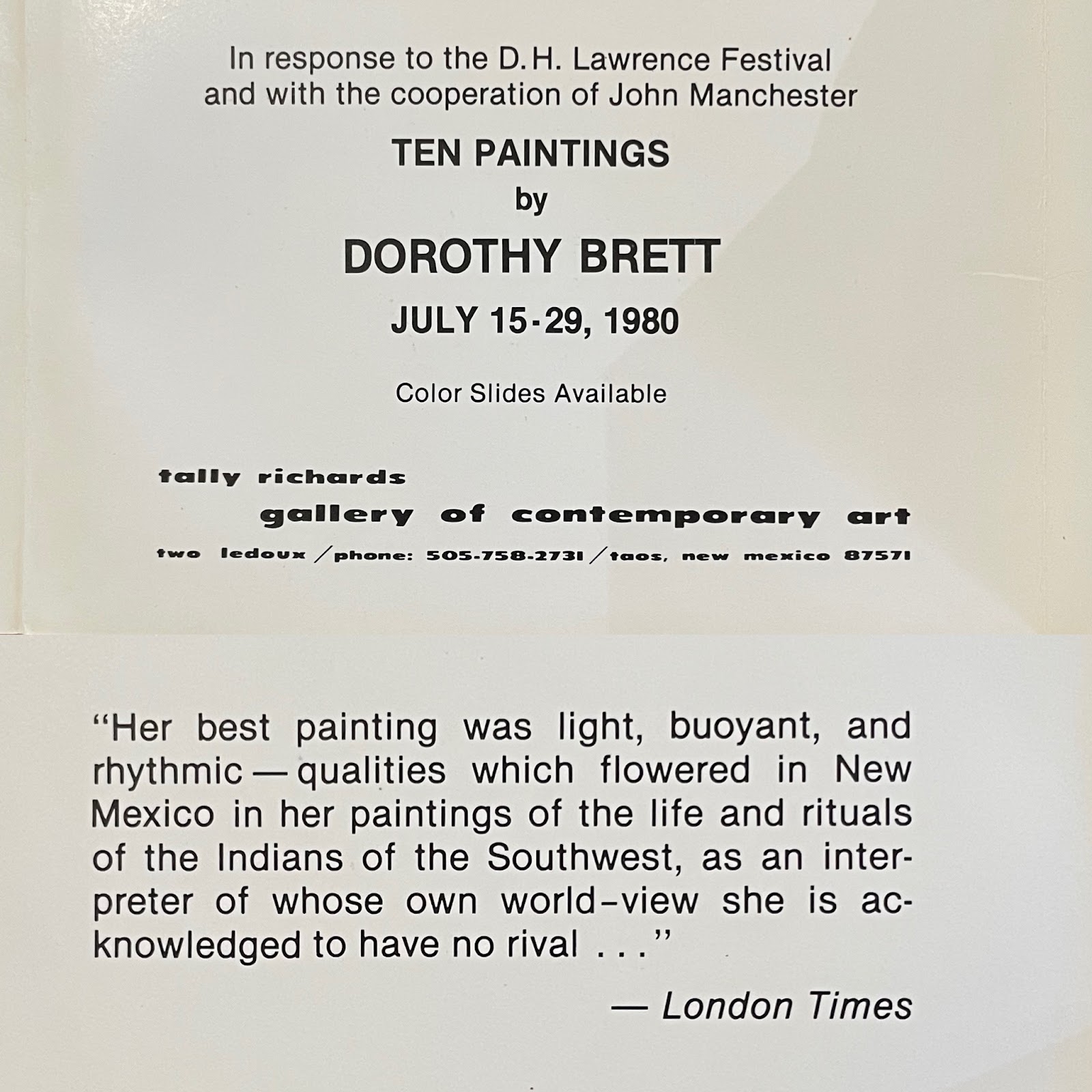

Through these last 100 years there have been four retrospectives of paintings by Dorothy Brett in Taos & Santa Fe, the first was at the Harwood Foundation, Taos in 1959, a few years later at the Stables Gallery, Taos in 1967 “A Tribute to Brett” with just over 100 paintings by and of Brett borrowed from collections all around Taos.

In 1974 the Jamison Galleries of Santa Fe paid tribute to Brett with a small retrospective “Fifty Years of Painting in New Mexico” organized by John Manchester who at the time was the director of the Manchester Gallery, located next to Brett’s home in Taos.

In his writing a ‘Tribute to Brett’, author Frank Waters wrote:

“But Brett is more than a painter. …she has stubbornly resisted being pinned down like a butterfly. She exists as an original in her own right. An ethereal spirit embodied in a bright red greatcoat and a small hat overloaded with trinkets, her whisky white hair and wrinkles, her picayunish faults and atrocious memory. But only to remind us again in person that joy and love and wonder are attributes of man’s eternal Spring, not the Winter of his discontent. Brett’s presence here today announces the 50th anniversary of the arrival in New Mexico of a blithe and childlike spirit from the other world woods and moonlit glades where elves and fairies dance.” 1974, (an essay from the catalog).

This past year the Millicent Rogers Museum, Taos held the exhibition “Painting from Within, 100 Years of Dorothy Brett in Taos”

“The paintings Brett created in Taos had a difference from her contemporaries of the Taos painters, ephemeral, awash in light and color, full of movement and form. She learned every nuance of Puebloan ceremonials, documenting them in her paintings of ceremonies through memory. Brett never relied on photography, although some believed her to do so as her depictions were quite spot on. She would check in with her Pueblo friends among the Taos people to ask if she’d got it right in her paintings.

Brett has remained under the radar of curators and art collectors for far too long. Much like Hilma af Klint, museums, curators and the public alike are searching for that extraordinary ‘undiscovered’ female artist. In the far away land of the Taos art colony, the Honorable Dorothy Brett’s time is now.”

excerpt from my catalog essay for an auction on November 1, 2023 at Hindman of “Deer Hunter” a 1967 Brett painting which set her auction record to that date at $25,200. (the new auction record is now at $35,000.).

The punched tin cutout of the Phoenix Rising which Brett made and placed on the Lawrence Tree, as the tree grew the tinwork was removed and placed on the porch fence of the main house at the Lawrence Ranch

“For recording Indian dances in paint we must rely on Miss Dorothy Brett. No one is better fitted for this labor of love. With her ear trumpet and fishing pole stuck in her “dream of beauty” (a station wagon she can nap in) Brett has rumbled over every road, poked up every canyon…

There is something strange, ineffable, and compelling about Brett’s Indian paintings. They are not portraits like Fechin’s, with their wonderful, realistic characterization, their vivid colors and bold, broad style. Brett is the only painter I have known who has blindly, intuitively caught the valid, mystical component of Pueblo character.

After twenty years, Brett has developed a style which identifies her paintings as far as you can see them, and a style that suits her subject perfectly.

So far, in her new series, she has done the Deer Dance, the Buffalo Dance, the Turtle Dance, the Matachina, and the Feather Dance. There is no describing them. The dancers are alive with the spirits of their masks; they are a whirl of feathers, a maze of tossing horns, a moving phalanx of irresistible power, a fantasy of ancient Spain. And yet the background figures are so warm and earthy and realistic we can pick out the faces of our Pueblo friends. All are compactly composed, balanced of color. They are Indian to the core, and they are Brett.

Every day she gets Trinidad, the best dancer, to come to her house:

“We spend the mornings going into the patterns of the dances, the details of the dress and so on. Damn it, all these years I’ve been held to that rule of no photographs, no drawings and so on. Then all of a sudden it seemed worthwhile to take the risk of offending the old men to record these dances before they disappear, and of course I should have started years ago, but I suppose one never starts anything until one is ready. These Indians are so funny! (He, the war chief) came up to me at the Turtle Dance this time and said, “Now you put away that camera!” (referring to her hearing aid) knowing it was my ears, his idea of being funny and how he laughed… I have most of the ingredients for the Races. I want to do the Pueblo as we know it from the old days… you remember how the colour piled itself up, and below the runners, and then a hint of the aspen tree altar… After that with the help of Trinidad I may try to do some of the old dances they never do… We will pass off the scene but we have seen the heyday.”

That heyday of Pueblo dancing, as well as it can be framed, will be remembered in Brett’s paintings.”

from ‘Masked Gods, Navajo and Pueblo Ceremonialism’ Frank Waters 1950

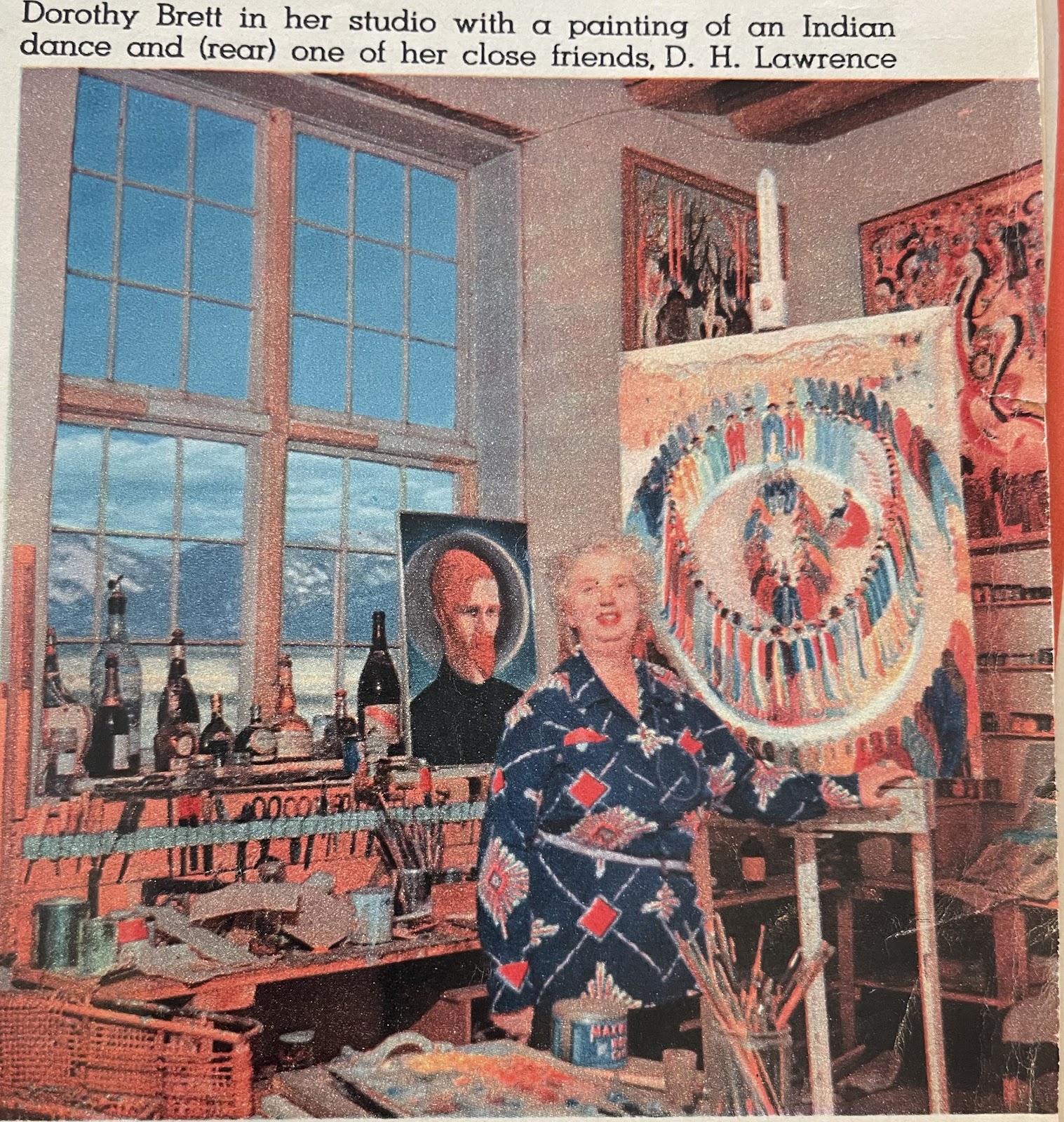

Brett at home in her studio

Brett's work table from her studio which I acquired from Ouray Meyers

The following excerpts are from a tape recorded interview in September 1966 (possibly for CBS or NPR Radio) by Erik Bauersfeld (June 28, 1922 – April 3, 2016) of the Right Honorable Dorothy Eugénie Brett (10 November 1883 – 27 August 1977)

Myself with Eric Baursfeld discussing DH Lawrence, Dorothy Brett and his roles in Star Wars.

EB We turned our attention at that point to a painting by Brett of Lawrence which I had often heard discussed. In the work Lawrence is seen as Christ on the Cross, he’s also seen as a ‘pan-like’ creature on the lower right looking up at the Christ. Brett explained these two aspects of Lawrence.

DB You see it’s the two aspects, the Christ-like aspect that Lawrence had and the Pan aspect. This Pan aspect was always duly at the Christ aspect. (whispers) He was afraid of the Christ aspect, I think.

EB Not the other way around?

DB No he was afraid of the Christ aspect. Afraid of getting his feet off the earth you know. I think, I never have quite undressed why, he seemed afraid of it.

EB Why do people laugh at your interpretation of Lawrence as both, the Pan and the Christ figure?

DB Because they still think he’s a sort of demoniacal person, you know. This person always flying into tempers and so on. They missed the subtlety of the man. His awareness, his powers of observance, he was so observant, so aware. They missed all that side of him.

EB There was a quotation in your book, “If you are Nervous in the night, don’t light a candle, but lie and look at the stars, the stars will take your fears away.”

EB The ‘Upstairs’? What does that mean?

DB The Upstairs means the world of what… what would you say, the world of, of Spirit. You know, the unseen world.

EB Yes, yes.

DB The unseen world, though few people really believe in.

I think I see everything always in pictures to me. Everything is a picture to me, even in the past.

EB That’s a nice switch because in your paintings, one way you describe the paintings of the indians is that you’re painting the way they see themselves. From the inside…

DB I’m not interested in what I call appearances anybody can do that. Appearances, just mere appearances. I’m interested in the attitude of life. Of the indians, of people, you know inner, inner spirit. That’s what I try to get. Which is so hard for a camera to get. Sometimes I’ve seen photographs of someone who is capable of bringing up that inner thing and showing it, you see. It’s very, very rare, usually a photograph is just a photograph, however good. I think Alfred Stieglitz (January 1, 1864 – July 13, 1946) could do it. But it requires, it requires the person who’s being photographed. They’re the ones who have to do it. Who have to get themselves into that condition, or whatever it is.

EB …in your painting you do get at the inner quality of the indians. Practically everything that I see, I think no question about that. In the portions of the autobiography I was looking at, you talk about many other people. Will you be talking in some way about yourself? The way you paint for instance, the indians?

In painting Indians when you first began to do this, you had to work in a style that was different than what you’d done before… You were seeing them as they saw themselves. Understanding them that way, but that meant a change in style of work. Was that true?

DB What I feel about style is that there’s a tremendous danger in clinging onto style rather than clinging onto what you’re trying to say. Sometimes you can not say it the same way. You can not really paint a person the same way you paint a tree, do you see what I mean. So often people cling to their techniques and their style. I think that’s a great danger, don’t you? It’s what you’re trying to say that’s important, not the way you say it.

EB Do you recall a drastic change in the style of your work?

DB I’m trying to think back now on the paintings I did in those old days. There was always that in it, but it wasn’t so developed. There was always that in it, that attempt to get the content, whether it was a portrait or whatever it was. Of course when I first came here, I do think that nobody thinks I have any technique or any style at all.

EB Who says that?

DB I think most people say it, or think it. I think there has been a steady constant change, because what happens is that you suddenly realize your point of view, your attitude. Then your technique towards that attitude begins to develop and improve. You begin to know how to do it. You fumble around and fumble around and then you begin to find out how to do it, you see. For instance the painting I’m doing now of the Circle Dance, it’s called the Friendship Dance too. It’s a culmination of finding out how to do it. the technique how to do this thing that you want to do. It’s a slow development, a slow thing. I fumbled around my first painting of indians. I was painting the Rabbit Hunt up on the ranch, oh years ago. Mabel came up, Mabel wanted to see it and it wasn’t finished. I was very hesitant because I was very suspicious of her you know, I thought she would be kind of snide about it. Well finally she sort of pressed me to show it to her. So I took the sheet off it and showed it to her. I can still see the expression on her face of astonishment, because she saw, she understood what I was feeling about the Indians and what I had got even then about the Indians. Since then you see the whole thing just develops and develops and develops. You develop that painting, what you’re after.

*“By 1927 Brett had started painting the Indians and their life in earnest. Her first large painting, which she kept very secret until it was finished, was the Rabbit Hunt. She finally consented to show it to Mabel, who was quite surprised at how good it was, and insisted Brett show it in the one gallery (Taos Heptagon at the La Fonda Hotel in Taos Plaza) that was at the time in Taos. When the gallery group rejected it, Mabel (who was an important patron to them) stormed in, demanding that they let Brett show with them. It is amazing that the majority of the Taos Painters have never taken Brett’s art seriously, yet not a few of them have consistently attempted to imitate her work.”

John Manchester in an edited epilogue to ‘Lawrence and Brett, a Friendship’ 1933-1974

EB Did the Indians in any way influence this interest of yours, upon first confronting them, being with them, anything in their behavior or in their ways…

DB Certainly because the indians finally, the Indians have said, ‘That is us, that is what we are.’

EB Do you think you would have done that if you hadn’t seen indians? Is it the indian themself or this type of people that really set you going in that direction?

*In England Brett first saw Indians included in Buffalo Bill's Wild West performances in London. Which were part of the American Exhibition for Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee at Earl’s Court on May 9, 1887. Brett would have been 3 1/2 years of age.

EB I’ve noticed in your more recent paintings, by the way you paint daily and continue very vigorously to paint, and in the new paintings that you’ve done, I notice another change of style. They seem to be more vigorous, more vivid in the contrast of color, more intense in composition.

DB Which I think they are

EB For instance the ones I’m looking at right now are two dances and the Snake Dance. Right beside it is one you’d done much earlier, which is an extraordinary painting I think, a whole line of dancers in the upper portion, the lower portion there’s mainly a piece of blip(?), but on the far right you see the medicine man in a cave.

DB The whole story of the Snake Dance is very involved, very long. It’s a long, long story of a young man who goes into the river. It’s a very long story.

EB In this new painting of the Snake Dance, there’s only two dancers.

DB Two Snake Chiefs, No, there’s a snake painted and what they call the teaser. The teaser is the man who has the wand and tickles the snake if it gets angry and going to bite you, when it throws out its venom.

EB That one plus there’s two birds over here, this is more recent isn’t it? That also has this new intensity more vigorousness, maybe even some idea…

DB Yes, the magpies. Maybe they’re my swan song?

EB Swansongs? These are Magpies Brett!

DB Final effort, before I kick the bucket and take off. I think I’m aware of something that I’m trying to get over before I, you know depart this life. I’ll tell you what I’m attempting, I think that we separate the thing that one’s doing, the indian from the surroundings. I’m trying to bring the surroundings, you see, when you do a thing for instance the Circle Dance and other dances out there and other things. They’re not just in a sort of sloppy, sloppy landscape. I’m trying to bring all the flowers, and the trees into it, to make a complete whole of the thing. Here they are doing the Circle Dance but at the same time here are all the flowers and the tress and everything, in which they are dancing. In most paintings, the backgrounds are just, the landscape is just a background and that seems to be very dull. There is an extraordinary dance because these Snake Priests look so savage. They’re so wild and they’re so savage to look at. The dance itself is a cradle song, it’s a love song to the snakes. The most beautiful rhythm to the snakes, like rocking a cradle. It’s a love song to the snakes. They have the snakes for two weeks and they wash them and talk to them and sing to them and all that. Then they dance with them. The dance is this simply marvelous beautiful cradle song, it’s just such a lovely rhythm. You ought to go and see those things they’re worth it. Despite of the tourists that were quite…

*Brett lived another 11 years.

EB What part of the year? It’s not unusual for the subject matter, an artist is interested in, to play back upon his own life, to transform it in some way. I wondered if these dances, these rituals have done that to you?

DB August. I think so, a bit yes. I’ve watched Trinidad (Archueleta) planting. In the old days up at the ranch when he was up there. Now, he would plant an ordinary potato, which seems to me to have no charm, but the way he did it, it was almost a religious act. To make the whole… the way he put the potato in, the way he covered it up. He put, so much reverence. It was really almost a religious act. You see what I mean. Their reverence for what gives them food, for the water, for the river, but what do we care? You take a tractor, do you think a tractor has any kind of, a man who drives a tractor they just throw corn out of a machine, it isn’t the same thing.

Dorothy Brett, 1959

‘Soon after she settled in Taos, she began to paint the Indian life with a vision of it quite different from any we had heretofore seen. Her line is so individual one can recognize it among those of a hundred others. Her Indians are subtle, wild and sweet, with the slant-eyed look of fawns; her Indian men are frequently boys riding ponies, with gay blankets blowing as they sweep on; or they stand shrouded in the white sheet in half-open doors, the dark triangle of the upper face mysterious in anonymity. Her women are intensely feminine, always dancing, or baking bread in their round outdoor ovens, or bathing babies in the sunlight with star-spangled flowers sprinkled in the grass about them. She has a real feeling for this already and makes it glamorous (as maybe it is) and always stylish.’

“Taos and Its Artists” Mabel Dodge Luhan 1947

'My Three Fates' Mabel Dodge Luhan, Freida Lawrence, DH Lawrence sitting at the Lawrence Tree, Dorothy Brett wearing her hearing aid 'Toby' at her typewriter (Albuquerque Museum collection)

In the mid 1800’s anthropologists and others began to document what at the time was referred to as ‘the vanishing race’. Edward Curtis, Frank Cushing, Elsie Clews Parsons among many others recorded through photography, paintings, writings, and collections of artifacts the American Indian. Today much of this material of Native American history has been set aside as per misunderstandings of intent, yet the documentation in many cases is all that is left. Taos Pueblo elders recommended that a recent museum exhibit refrain from including Brett’s paintings depicting indigenous subject matter of ceremonies or dances. Yet four of the paintings included were depictions of the sacred Taos Blue Lake, (am I possibly the only one who was confused about this?). This purposeful omission of the paintings of ceremonial dances was akin to censorship. The quote ‘Tell me no secrets, I’ll tell you no lies’ comes to mind which is interpreted as if I answer your question truthfully, I would either offend you, or give you information that you are not allowed to have. Brett creates a point of view as an observer (at times a birds-eye view), figures are often depicted with their back to the artist. She gives away no secret knowledge, only depictions of what she has witnessed during open to the public events.

Historic and accomplished Taos women artists include Gene Kloss (1903-1996), Ila McAfee (1897-1995), Beatrice Mandleman (1912-1998), Barbara Latham (1896-1989), Catharine Chritcher (1868-1964), Mary Greene Blumenschein (1869-1958), Helen Blumenschein (1909-1989), Pop Chalee (1906-1993), Eva Mirabal (1920-1968), Rebecca Salsbury James (1891-1968), Dorothy Benrimo (1903-1977), Gisella Loeffler (1903-1977), (Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986) and Dorothy Brett (1883-1977).

The record setting Brett painting 'Indian Women Watching Horse Race' which sold with fees for $43,050.

Display of Brett paintings auctioned at the Santa Fe Art Auction

Fourteen paintings and drawings by Dorothy Brett included in the Santa Fe Art Auction on November 8 & 9, 2024 were sold mostly over their high estimates between $900. - $35,000. (a new auction record for the artist) this is an average sell price of $9,000.

Brett portrait by RC Gorman (private collection)

“The beauty of the country I have never succeeded in getting across to you or anyone who has not seen it for himself.”

Elsie Clews Parsons